Anyone who has read a few of my posts probably knows that I strongly believe that public school teachers need to have the power to remove disruptive and apathetic students from their classrooms. I am convinced that doing this would do more to improve public education than any other "reform" that has been proposed in the last forty years. Many teachers have told me they agree with this, but the question I consistently hear is, "What are you going to do with the kids who get kicked out?"

My gut reaction is always to reply, "I don't care! I know where I don't want them!" but I know how harsh that sounds, so let me explain. If a student is unwilling to make any effort to learn, there is nothing to be gained by having that student in school. But every student effects other students, and the only effect that student can possibly have on his classmates is negative. Some disruptive students might gain something from being in class, but the negative effect they have on their classmates far outweighs that. We keep on claiming that we, as a society, believe that education is very important. If we really believe that, do we want to put people in classrooms who are clearly damaging the education of others simply because we can't think of anywhere else to put them? We can argue about what the purposes of public education should be, but there is no way that one of those purposes should be to provide babysitting services for kids who won't try and won't behave.

Before I go on, I should point out that I'm not talking about a lot of kids here. I'm not talking about kids who talk a little too much or fail to turn in their homework once in a while. I'm talking about kids who are constantly disruptive, and kids whose effort is so poor that it becomes clear that they have no chance to pass. In Philip K. Howard's excellent book,

The Death of Common Sense, he says that teachers in even so-called "bad schools" report that it is a relative handful of kids who cause most of the problems. There should be an effort to turn disruptive and apathetic kids around, but there comes a time to say, "Enough!"

Removing the most disruptive and apathetic students would greatly improve the learning environment in public schools. First of all, we'd be removing the most disruptive and apathetic kids. (Duh!) But the effect would go much further than that. Very often, the most disruptive kids have a certain amount of charisma, and they are able to drag some other kids along with them. Get them out of the schools, and many of those other kids will be much less of a problem, and some of them will be completely fine.

The number of problem kids in schools would be cut down even further, because many of the kids who now perform and behave poorly want to stay in school. Some of them want to graduate, and some of them enjoy the social aspects--they want to be with their friends. Many of them are kids who are willing to push the limits, and they've found out that nothing serious will happen no matter how badly they behave and no matter how poor their effort is. If they knew getting kicked out was a realistic possibility, their effort and behavior would improve.The last really disruptive student that I had fit into this category. He behaved badly because he could. He seemed to enjoy being scolded, detention scared him about as much as a French Poodle would scare and axe-murderer, and he viewed suspension as a vacation. He was a fairly bright kid, though, and he wanted to stay in school. I have no doubt that if he'd have thought he might get kicked out, his behavior would have been much better.

My point here is that many of the kids who now behave badly would not end up getting kicked out. In fact, we'd be doing them a favor by giving teachers the power to remove the most troublesome kids from their classrooms, because their educational performance would improve. But what about kids who do get kicked out? Here are my options:

1. The most obvious solution is to place them in alternative learning centers. One problem with ALCs, however, is that they lessen the incentive for kids to avoid getting kicked out of their classes. Too many students don't mind the idea of getting sent over to the ALC, so they can be with their buddies. We have an ALC in our school district, but because it is so convenient for the students who get sent there, it doesn't help our schools as much as it should. We still end up with too many kids in our regular classes who don't behave or try as hard as they should. Nevertheless, having an ALC is definitely better than nothing.

2. SLM, who I disagree with on just about everything that has to do with education, suggested in a comment over at Education Wonks that we bring back "reform schools" for kids who refuse to fit into normal classrooms. I like this idea. We already have these kinds of institutions for kids who get into legal trouble (we call them "training centers," here), so why not also use them for kids who refuse to do what is expected in school. Reform schools would not be pleasant places for students to be sent to, and I don't think they should be.

3. Another public education critic, Peter Brimelow, in his book

The Worm in the Apple, argues that we should find a way to give more meaning to the GED so that those kids who want to get out of school and into the working world can do so. Brimelow is another guy that I disagree with on just about everything, but I have no problem with this idea. If someone can't wait to go to work in a factory, I have no desire to force them to sit in my classroom so I can make them miserable, and I certainly don't need them there so they can be making my life and those of my other students' miserable. The problem with this is that I suspect a reason employers don't put much stock in the GED is that they know that many people who get them couldn't make it through school because they wouldn't show up, wouldn't be on time, and wouldn't follow directions. Those aren't exactly the traits of an ideal employee. That being the case, I'm not sure how we go about making the GED more meaningful.

4. The argument can also be made that kids who choose not to behave or not to try should become the responsibility of their parents. After all, we are now in the 21st century, and there are all kinds of materials for homeschooling on the Internet. State legislatures around the nation have been doing everything they can to promote homeschooling, and as far as I'm concerned, these kids are great candidates for that option.

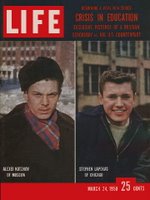

5. Finally, if kids who have dropped out or gotten kicked out of school have a change of heart, and decide that education does have something to offer them, I would love to see them come back. If we are going to spend money, I would rather spend it on programs to encourage kids or young adults to do this, than to spend it on the education of kids who are forced to be in school, but don't want to be there. Regardless of their personal history, it seems to me that we have our best chance to help people when they have decided that they want to participate in their own education. Time Magazine's "Dropout Nation" cover story in April told the story of one young man who had done this. A number of years ago, 60 Minutes did a feature on a program that encouraged dropouts to come back to school in Chicago that seemed to be working. I don't know if that program still exists, or if it ended up being considered a success or a failure, but I think the concept was a great one.

The bottom line is that our top priority should be to provide a good learning environment for kids who want to learn and are willing to follow reasonable rules. These are the kids that we can help, and these are the kids who deserve it the most. The first and most important lesson we need to teach kids, especially those with problems, is that they must try to help themselves. Somehow, some way, we need to find a way to separate the kids who refuse to learn this lesson from the rest, especially in so-called "failing" schools. Trying to turn around disruptive and apathetic kids is a noble endeavor, but when we focus too heavily on doing this, we have to ask ourselves if we are doing more harm than good. We have to ask ourselves if we are giving those kids who are trying to do the right thing a fair shake. I think the answers to these questions, especially in some areas of our nation, are painfully obvious.